Child's Play in Helen Levitt's Early Photographs

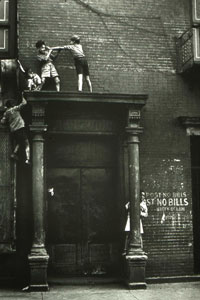

Figure 1: Helen Levitt, New York,

c. 1942

“The unconscious obsession we photographers have is that wherever we go we want to find the theme we carry inside ourselves.” —Graciela Iturbide, photographer

In 1936, Helen Levitt found a medium for her “unconscious obsession:” she began photographing children’s play in the streets of her native New York City. Wandering through working-class neighborhoods—looking for the right kind of “material” and “a proper shot,” as she puts it, by scouting street life in Brooklyn, the Lower East Side, Harlem, and the Bronx—Levitt uncovered hidden worlds playing out on stoops and sidewalks. The photographs she made early in her career (roughly 1936 to 1950) are preoccupied with children who fabricate, from the barest threads of the imagination, their own “strange weave of time and space,” to borrow a phrase from Walter Benjamin.

Levitt’s devotion to child’s play encompassed two aspects of the subject: the social complexity of children’s performative games and the untutored artistry of their drawings. Treating children’s anonymous graffiti, doodles, and drawings as quasi-surrealist found objects, she used her camera to amass a visual archive documenting more than 150 examples of naïve expressions scrawled on sidewalks, walls, and stoops.

Levitt’s in-depth survey of children’s art and play aroused keen interest at the time. Beginning in 1939, when her first photograph was published in Henry Luce’s Fortune magazine, her pictures garnered attention in a cross-section of publications. In 1943, the Museum of Modern Art granted her a one-person exhibit, “Photographs of Children by Helen Levitt”—a remarkable achievement for such a young photographer, especially since her medium had only recently been welcomed into the world of museums.

To understand why Levitt’s vision incited such interest, consider Figure 1. Made with a 35 millimeter Leica, the photograph suspends an instant of time; conjoining urban space and gesturing bodies, it infuses an arresting sense of solemnity and grace into a scene from everyday life. Positioned between home and street, private and public, the real and the fantastic, the three children are experimenting with alternate identities afforded by the most rudimentary of props—a piece of cloth with eyeholes cut out to make a mask. Their play is marked by an ephemeral artfulness, an emphasis on the act of viewing, and an urban context; it thus presents an emblem of the street photographer’s practice: they, too, are heading out into the city, flâneur-style, to partake of strange spectacles.

Play is fun, the picture declares, but deeply serious. That nuanced, dialectic sense of the subject is central to Levitt’s achievement. In her thoughtful approach to urban children’s play, Levitt found a way to negate reigning assumptions about childhood, urban social life, and photographic representation, while simultaneously speaking to her cultural moment.

Figure 2: Advertisement from Minicam

magazine, vol. 6, March 1942

Levitt was far from alone in discerning a new salience in the figure of the child. During the 1930s and 1940s, a child mania swept through American culture. A torrent of photographs, paintings, exhibitions, books, movies, and articles made children newly visible as objects of study, ideals of contemplation, and targets of political policy. For example, the culture of photographically illustrated magazines that burgeoned in the 1930s habitually purveyed sentimental photographs of appealing innocents (Figure 2). Framed as the rationale for purchasing products ranging from cameras to cars, photographs of children became one of advertising’s favored icons of consumer pleasure and domestic prosperity, in a decade marked by catastrophic levels of unemployment and bankruptcy. At the same time, mass culture images of children were used to symbolize vulnerability and suffering. Children appear repeatedly in the archive of documentary photographs made for the federally sponsored Farm Security Administration’s photographic projects. To take two famous examples, children constitute the focal point of both Dorothea Lange’s 1936 Migrant Mother and numerous portraits from Walker Evans and James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. For both Evans and Lange, the helpless child embodies the harrowing extent of socio-economic distress.

Whether such popularly circulated pictures celebrate childhood or mourn its betrayal, they trade on culturally sacrosanct notions of children as pure innocents needing shelter. Such notions affirm ideological claims for traditional gender roles, domestic norms, racial homogeneity, and the glorification of “the family.” Levitt’s photographs undercut precisely these reigning myths of the child as an unproblematic personification of innocence and symbol of respectable family and social life (though her work displays no lack of tenderness toward its subjects). Levitt devised an account of child subjectivity that insists on complexity, diversity, and contradiction. She represented children as active agents, self-consciously experimenting with social roles and manifesting a remarkable range of affect. Her photographs show children running wild with physical pleasure, or withdrawing quietly into states of reverie; the graffiti signs she collects are ribald, bizarre, aggressive, or charming. Drawing upon the 35 millimeter camera’s capacity for multiple, rapidly sequenced views, Levitt crafted a visual essay that deliberately refuses easy answers to its central motivating questions: What is a child subject? And what makes child’s play significant?

In probing these questions, Levitt made the crucial decision to center her attention exclusively on working class children. Signs of social class include clothing—plain gingham dresses, a coat held together with a safety pin, scuffed hand-me-down shoes big enough to “grow into”—as well as the urban environs that provide the theater of action for Levitt’s players. Her subjects are situated against graffiti-covered walls, in empty lots, and in rubbish-filled alleyways. She also envisions a thoroughly heterogeneous population of New Yorkers, insisting that race is a dimension of class in American culture while refusing to map stable racial classifications onto urban geography.

By focusing her lens specifically on the urban street child, Levitt revived an iconographic tradition that gained significance in nineteenth century realist traditions concerned with the fate of the urban poor. A classic literary example is Nana from Zola’s L’Assommoir, who embodies the degradation that results from her parents’ poverty. Nana’s unsupervised games in the street are, in Zola’s telling, a symptom of and catalyst for dissolution:

Her latest brainwave was to go and play in the blacksmith’s opposite, and there she would swing all day on cart-shafts, hide with gangs of guttersnipes in the dim recesses of the yard, lit by the red glow from the forge, and then suddenly tear out, shouting, disheveled and filthy….

Helen Levitt, New York, 1939

Zola’s “guttersnipes” would recur in late nineteenth and early twentieth century documentary photographs depicting the lives of the urban poor for comfortable audiences. For example, the journalist and lecturer Jacob Riis—famous for his lantern-slide lectures and publications about poverty in New York—made the street child a focus of anxiety in books like How the Other Half Lives (1890) and The Children of the Poor (1892). A generation later, the camera man and dedicated social reformer Lewis Hine would photograph street children’s work and play repeatedly to critique an economic system willing to exploit child labor.

The trope of the street child may have roots in Zola, Riis, and Hine, but Levitt reconfigures its connotations. Poverty, in her account, is not debilitating, and the urban poor are not simply objects of reform or sociological investigation. Her children are not depraved, as in Zola’s novel, nor abject, as in Riis’s photographic exposés; nor are they helpless objects that arouse pity (Hine, Lange, and Evans).

The difference in her account emerges from the sophisticated ways in which she uses space—visual, geographic, and social—to inflect her subject. She insistently organizes her pictures around specific sites of urban life: the stoop, the doorway, the window, the vacant lot, and the curb. The transitional zones of urban geography provide the framework of her photographic messages.

Levitt’s consistent and canny framing of play-scenes makes the picture itself into a space of play. Her self-reflexive concern for the production of transitional space anticipates D. W. Winnicott’s fundamental observations about child’s play, articulated in his object relations psychoanalysis: that play constitutes the unfolding of a transitional zone between inner and outer experience, reality and fantasy, self and other. In a sense, Levitt conceived the spatial-temporal art of photography as a transitional phenomenon. Among the most intriguing statements Levitt has made about her work is that she aimed “to photograph people outside as if they were inside.”

Levitt, a largely self-taught photographer who dropped out of high school shortly before graduation to pursue the more adventurous lessons of the city’s streets, probably had little or no formal exposure to object relations theories. Rather, her acute attention to space and her receptivity to her subjects’ variable, complex, and autonomous worlds allowed her to discern, with great acuity, the phenomenology of play, using the camera as her instrument of investigation. Her best work achieves what Walter Benjamin, quoting Goethe, called “the delicate empiricism that becomes true theory.”

Elizabeth Gand is a doctoral candidate in History of Art at UC Berkeley.

This article can be found in the February/March 2009 newsletter.