Art in a State of Siege

Almost 30 years to the date after handing in his Berkeley PhD dissertation, Joseph Leo Koerner returned to campus in March 2018 as the Avenali Chair in the Humanities. During his visit, he presented a lecture, symposium, and film preview, all of which addressed the topic of “Art in a State of Siege.”

Koerner’s first event, a lecture entitled "Art in a State of Siege: Bosch in Retrospect," used Hieronymus Bosch’s triptych Garden of Delights as a focal point to discuss various intersections between art and lawlessness throughout history. The meaning of this bizarre and inscrutable work had eluded viewers and art historians for centuries, until twentieth-century German art historian Erwin Panofsky made major breakthroughs in deciphering its iconography. Panofsky’s work was profoundly shaped by developments in political and moral thought that occurred during the state of siege under Nazi Germany. His scholarship therefore raises important questions about how contemporary historical events can inform the interpretation of art created under similar circumstances in the past. Panofsky’s understanding of a twentieth-century “state of siege” was an important tool for approaching Bosch’s own interpretation of the theme.

On the second day of his visit, Koerner led a symposium and was joined by History of Art professor Whitney Davis, Classics and Rhetoric professor James Porter, and Jane Taylor of the University of the Western Cape in South Africa. This group of scholars had an opportunity to expand upon the notion of art in a state of siege, tracing the concept through disparate time periods and across disciplines. Together they explored the function of art under siege in diverse works such as those of South African artist William Kentridge and the Greek poet Homer.

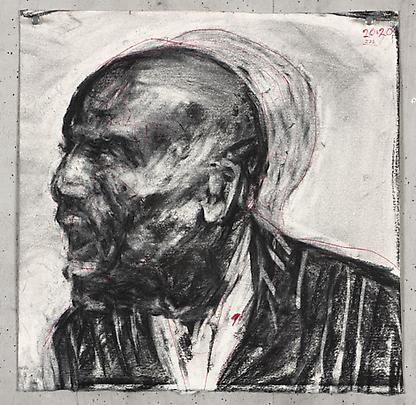

The final event, a preview screening of Koerner’s documentary film The Burning Child, revealed the filmmaker’s personal connection to art in a state of siege. The film portrays Koerner’s return to the city of Vienna to explore and reflect upon his father, the painter Henry Koerner, whose life growing up in Vienna was severely impacted by the Nazi occupation. As he learns more about his ancestors, as well as about the heart and soul of Vienna, Koerner comes to reflect upon the Viennese reverence for the “beautiful home” as embodying both an ideal and a repulsion, a mixture of dream and reality.

A recurring motif throughout these events involved the relationship of art and memory. In both the symposium and the film, Koerner discussed an uncanny object from his childhood — one of his father’s paintings, entitled My Parents, which hung above Koerner’s bed as a child. The painting of his grandparents featured in the background the apartment the Koerners would eventually inhabit during their summer returns to Vienna, perplexing the young Koerner as to how his father could have seemingly predicted the family’s future residence.

Koerner’s reflection on his father’s apparent ability to foretell the future eventually led him to consider the work of psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, who lived and worked in Vienna. Freud’s fascination with the unconscious and the uncanny, or the familiar that becomes unfamiliar, sparked the emphasis on memories, childhood, and dreams that pervades his work. According to Freud, repressed memories often manifest themselves in the form of repetition, causing people to repeat rather than remember — which led to one of Freud’s major writings, “Remembering, Repeating, and Working-Through.” From his office, symbolically located within his own home, Freud attempted to help his patients remember their past and overcome it, rather than repress it or manifest it in negative ways.

The reliving of repressed memories, based in a particular time and place, can be a dangerous and possibly violent activity, which is why Freud felt such memories must be experienced in the safe space of play. This idea led Koerner to explore the work of William Kentridge, a South African artist whom Koerner considers a champion of play. Working under South African apartheid, Kentridge became very familiar with a particular state of siege — though the version he experienced was more of an internal, psychic threat, in contrast to the siege experienced during WWII or under the Habsburg invasion of the Netherlands.

It is from William Kentridge that Koerner gets the theme of “art in a state of siege.” In 1988, Kentridge produced three silkscreen prints entitled Art in State of Grace, Hope, Siege. These overtly political works of art challenge the relationship between law and art. Professor Taylor, a South African scholar and author who is intimately familiar with Kentridge’s work and the world that inspired it, commented at the symposium that Kentridge did not believe in utopian or Platonic notions of finding the truth. This led Professor Porter to draw a connection to Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, a story where prisoners perceive only shadows of objects rather than the real thing. Art, as an embellished reflection of the real world similar to the shadows, has the ability to become more suggestive than the image or idea it conveys. The ability of the artist to distort an object by casting light onto it emerges as a theme in Bosch’s work as well as in Kentridge’s.

Koerner’s ability to synthesize art from such disparate historical periods as the Northern Renaissance, Nazi-occupied Austria, and 20th century South Africa into a single study comes from his unique perspective on art history. As Professor Davis pointed out, rather than focusing on art history as a linear progression, Koerner views art and identity as embodied by a spinning motion — a circle of interpretation. He prefers to study the mixture of past and future, which attracts him to images of circularity such as Bosch’s “Tree-Man” and Hans Baldung Grien’s “Bewitched Stable Groom.”

The events of Joseph Koerner’s visit were unified by an overarching interest in what it means for art to be created in a state of siege, when that state is understood as both an internal personal struggle and an external historical force. Across time periods and continents, artists use different forms of art as a way to remember, explore, and come to terms with the darkness of their particular age. Art manifests itself as a way to symbolically explore the impact of siege and to challenge the circumstances that threaten to bind the artist.