Remembering Print

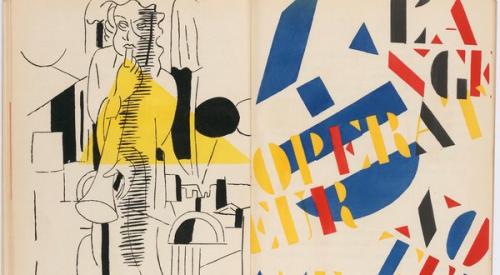

To the left you see a reproduction from Blaise Cendrars’s 1919 book ‘‘La fin du monde, filmée par l’ange,’’ designed and illustrated by Fernand Léger. It stands as the lead image for a February 12 article in the New York Times's arts section, "The Beauty of the Printed Book." Ostensibly an article about “The Printed Book: A Visual History,” an exhibition running through May 13 at the Special Collections department of the University of Amsterdam, the article opens, "Some things seem to designed to do their jobs perfectly, and the old-fashioned book is one."

From its start, this article set up the printed book as old-fashioned. Why?

Author Alice Rawsthorn writes, "From the oldest exhibit, which was published in Latin in 1471 by the French printer Nicolas Jenson, to the newest, 'James Jennifer Georgina,' Irma Boom’s poignant compilation of the postcards sent by a mother to her daughter every day for a decade, 'The Printed Book' presents a resounding defense of its subject. And it does so at a delicate time, when the traditional book is under assault from e-books, by which I mean both the electronic books that are downloaded on to dedicated readers like the Amazon Kindle, and the more sophisticated interactive books read on computers."

Having not seen the exhibit, I cannot tell if the curators frame the content as a response to the emergence of e-books, but one cannot help but notice the direction the New York Times's writer takes her article: it's a defense of the printed book built from a review of a museum show remembering print.

Have we moved so far away from printed text?

In defense of the printed book, Rawsthorn musters up numerous claims about e-books we've encountered before: "The design of e-books has been disappointing. Most of them look suspiciously as though their publishers have simply shunted their contents from print on to the screen. But some of the newer titles are more promising, largely because their designers have explored the technical and anesthetic possibilities of the new media."

Despite these unexplored possibilities, Rawsthorn argues, something about the printed text endures. "Yet there is still something," she writes, "very special about an adroitly designed printed book, perhaps because it is so simple and devoid of technological trickery."

And, perhaps, that is just it: a printed book is now considered simple. It's material; it's straightforward, and it can be an object of museum-worthy beauty. Is this, then, the future of the printed book? Rawsthorn appears to believe the printed book, as it looses ever more market share to e-books and e-readers, will have to stake its claims to existence on the aforementioned. Discussing the future of print, she writes, "The most probable scenario is that it [the printed book] will become a niche product with high design values, and is likelier to be an artist’s monograph or a special edition of a literary novel, rather than a textbook or pulp fiction."

And, perhaps, this is how we will remember print: as something beautiful and crafted. Save the pulp novels--the Hunger Games and the Twilights--for e-readers, but, if you want to buy a book in print, make certain it is museum-worthy.