From Close Reading to "Distant Reading" — and Other New Horizons for the Humanities

An article in The Chronicle of Higher Education last week reported on a research project at Stanford that, using Google’s rapidly expanding digital archive of the world’s books, brings serious quantitative analysis to the field of literary studies. Stanford’s Literature Lab, headed up by Franco Moretti and Matthew L. Jockers, is the first to make use of the vast digital library created by Google as part of that company’s controversial “Library Project.” Google has reportedly digitized over 12 million books in over 300 languages so far, which still represents only a small fraction of the books that have been printed since the invention of the printing press in the 15th century. Google aims, eventually, to digitize them all.

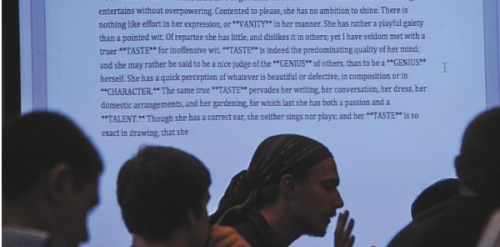

“It’s like the invention of the telescope,” Professor Moretti is quoted as saying. “All of a sudden, an enormous amount of matter becomes visible.” But new material requires new methods, and the technique of “close reading” that has hitherto prevailed in literary studies has here been set aside for what Moretti and Jockers call “distant reading” – a form of reading, in fact, undertaken by computers rather than humans. Researchers at the Lab use computer programs to track the appearance of certain topically related terms in large numbers of texts, for example in the tens of thousands of British and American novels published in the 19th century, only a tiny handful of which are normally studied. The technology brings into analytic (or at least statistical) view material that no human could ever hope to sift through.

On his blog, Jockers suggests that it is not that the Humanities are about to become hard sciences, but that new digital tools make empirical methodologies available that can address different kinds of questions about traditional objects of study. “What has changed is not the object of study but the nature of the questions,” he writes.

The ability to address hard "empirical" questions is presumably just one of the many possibilities digital library projects will offer Humanities researchers. What seems certain is that the rapidly developing digital archive will change the way many Humanities scholars do research; in what other ways remains to be seen.