Net Neutrality: What it Means for Humanists

If you've been on the Internet this last week, you probably saw something about "net neutrality." You might have heard that President Obama released a statement defending it as a crucial component to an "open Internet," while Senator Ted Cruz spoke out against it, calling it the "Obamacare of the Internet."

Should you worry over net neutrality? In a word, yes. All Internet users should. But scholars in the humanities and social sciences should take particular interest, given the issues at stake in this debate. Far from a wonkish technological squabble, the controversy over net neutrality has potentially profound implications for things that humanists care about deeply: media and communication, freedom and access, rhetoric and politics.

This blog post presents the debate over net neutrality as it relates to humanists and social scientists. Five issues stand out as particularly relevant to scholars. First, (the change in) net neutrality will drastically affect the ways in which scholars and citizens consume content, and what kinds of content they consume. Second, the controversy raises hard questions relating to the public/private dichotomy in American society. Third, the battle of net neutrality reflects shifts in the political war between old and new media. Fourth, it provides insights into the ways in which our society approaches "technical" debates, negotiating boundaries between the technical, the political, and the economic. Finally, questions over freedom, openness, and access are central to the debate over net neutrality; scholars who care about freedom of speech and surveillance in the digital age need to pay special attention to the controversy.

“A New Internet”

Why should humanists care about the net neutrality debate? The first and most pressing reason is that, to the extent that humanists use the Internet, changes in net neutrality will have profound implications on the ways in which scholars consume, produce, and share Internet content.

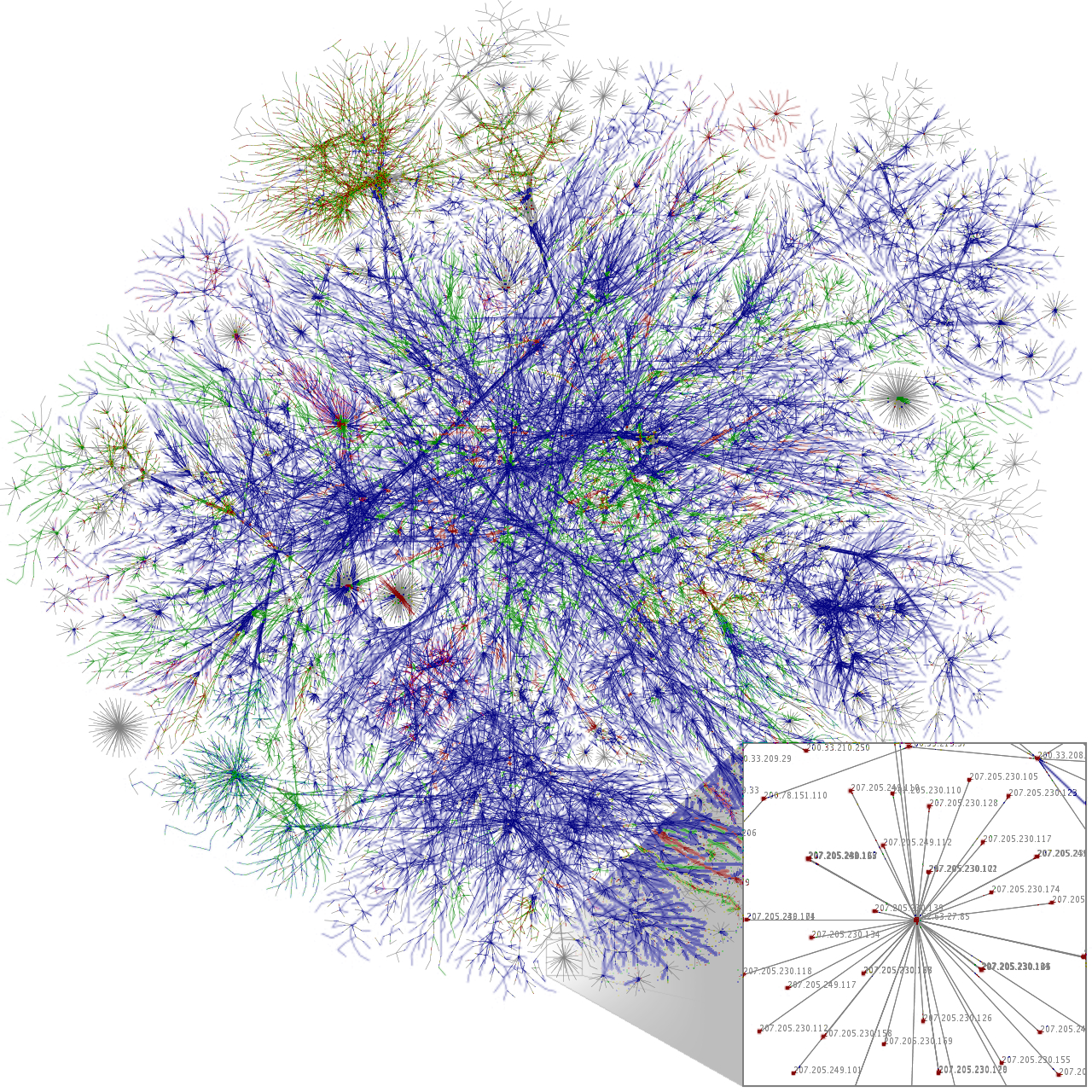

When you visit a website or stream a video, the content you see on your screen first has to go through an Internet Service Provider, or ISP. Because of the way the consumer market is, that ISP is most likely AT&T, Verizon, Time Warner, or Comcast. Under net neutrality, all data on the Internet are treated equally by ISPs. In other words, ISPs deliver all Internet content at the same speed, whether it’s google.com or your friend’s cupcake blog. While some question the details of this structure, most experts agree that net neutrality has been crucial to the development of the Internet since its creation. Importantly, net neutrality describes how the Internet works now; it’s the status quo.

ISPs invest heavy resources into building cyber infrastructure—the fiber cables, signal towers, and mysterious underground tubes necessary to bring you the World Wide Web. But the Internet has grown at a faster rate than Comcast can put down cables, and all that data-intensive content threatens to overload this infrastructure. The main culprit here is video streaming services and especially Netflix, which accounts for nearly 50% of all web video streaming. Companies like AT&T argue that Netflix should pay the cost for building a business that requires such a huge amount of bandwidth. “There’s no free lunch,” they say.

In order to solve this network problem and increase profits, ISPs want to overturn net neutrality in favor of a different kind of Internet than the one we’re use to. Instead of having one big broadband “freeway,” ISPs want to create a tiered model of service. Under this “new Internet”, ISPs can create “fast” and “slow” lanes that provide content at different speeds to customers, and then charge content producers heavy prices to get into the fast lane. This obviously favors huge corporate players over new start-ups; Google and Facebook can probably afford the fast lane, but your friend’s scrappy cupcake blog would probably be left in the dust

In the worst case scenario, ISPs can potentially break up the Internet into packages à la cable television. Instead of paying for generic data, you’re paying for specific websites.

While the above is an extreme possibility, it isn’t entirely unprecedented. Last year, Comcast reached a deal with Netflix in which Netflix paid millions of dollars to get its content to stream more smoothly. The agreement was controversial because Comcast was able to gain leverage over Netflix by throttling (or slowing down) the bandwidth of Netflix users. Once Netflix paid up, Comcast returned bandwidth to normal speed, thus leading Netflix executives to describe the whole episode as "extortion." Whether or not Comcast violated net neutrality is the subject of intense debate. But business and technology experts agree that the agreement sets a bad precedent for the principle of an open internet.

Those who support net neutrality, including big tech companies such as Google, Amazon, and Netflix, argue that neutrality is the leading driver of innovation and growth in digital technology, allowing for an open playing field. With net neutrality gone, the fear is that ISPs will have too much control over the content market. Because more than 77% of Americans have only one choice for high-speed Internet, ISPs can get away which such strategies even if it disadvantages consumers.

Is the Internet like Electricity or Cable Television?

Last week President Obama came out in support of protecting net neutrality: "We cannot allow Internet service providers (ISPs) to restrict the best access or to pick winners and losers in the online marketplace for services and ideas," said a statement released by the White House.

The problem, though, is that net neutrality cannot be protected without some kind of political intervention, and the battle over the “open Internet” is currently being waged in the bureaucratic labyrinth of the FCC. Obama’s proposal mirrored ones put forth by advocacy organizations such as the Electronic Frontier Foundation, urging the FCC to reclassify consumer broadband Internet service as a public utility, like water or electricity.

The plan would ensure new rules to protect net neutrality, including prohibitions on blocking (ISPs preventing you from accessing legal content), throttling (ISPs intentionally slowing down some content or speeding up others), and paid prioritization (ISPs discriminating against content providers that don’t pay a premium fee.)

Those who oppose the reclassification of the Internet as a public utility say they fear “government intrusion” into private markets. Broadband for America, an industry group, argued that the President’s approach would “vastly expan[d] the regulatory bureaucracy over the Internet.” Despite the government’s intimate involvement in the very birth of the Internet, there is now considerable pressure to keep Uncle Sam far away.

Supporters of Net Neutrality, a category to which the vast majority of tech innovators belong, have rejected this interpretation of the President's plan. Gizmodo calls it flat-out “wrong”, saying “The government will not determine the speed of the Internet, it will simply stop ISPs from slowing service down. Obama is asking private companies to treat their customers fairly; there is no part of his plan that involves the government seizing control of providers.”

As for the FCC, the agency signaled it would delay its decision until next year in order to deliberate further. But Chairman Tom Wheeler, an Obama appointee and a former cable/telecom lobbyist, said he did not plan to follow all of Obama’s proposals.

At the crux of this impasse, then, is the question over what constitutes a “public” good. Is the Internet more like electricity or cable television? Is it a luxury or a necessity to American public life? And if the Internet does constitute a prized national resource, what is the best way to protect that resource—through privatization or public ownership?

Ironically, whatever the FCC decides, the direction of the Internet will be determined by new government intervention. That is, either the government will regulate the Internet as a public good, or it will regulate it as a privately traded commodity. This fact draws on a classic humanist insight: that any public policy decision, including those to protect "free" markets, is determined by historically-situated understandings of governance. Thus, to the extent that the net neutrality issue is really just another version of the public/private debate, it prompts a discussion to which humanists are uniquely qualified to contribute: “what kind of country we want to live in”?

The Latest Battle in the War Between Old and New Media

If the net neutrality issue is really just the closing of a frontier, the new establishment will be decided in a raging battle between media titans. Specifically, it is a fight between new media (Google, Netflix) and old media (Comcast, AT&T): the latest in an epic war that that has already extended to journalism, entertainment and copyright law. This is not to say that other actors are neutral or unimportant. But the sheer amount of political resources deployed by these two cadres demonstrates the extent to which the fight over net neutrality is the latest (and fiercest) battle in the Media Wars, with the future of content at stake.

Not surprisingly, telecommunications and cable companies oppose the plan to regulate the Internet as a public utility, calling it “extreme” and taking dramatic steps to stop it. Their opposition will be influential, given the industry's reputation as a tough political player. But perhaps more interesting is New Media's dewy political awakening, and especially that of Google, who is turning its business acumen into political influence at alarming speed.

The shift in political power between Old and New Media raises interesting questions for humanists and interpretive social scientists, some of which we have discussed here at the Townsend Blog. Will the rise in New Media's political influence mean greater creative innovation and more democratic content production, or will it drive a closer—and more disconcerting—relationship between and private holders of big data and government surveillance? Is net neutrality the last defeat of Old Media, driving the industry the way of the fax machine, or will it signal Old Media's return as the gatekeepers of mass culture?

Democracy, Partisanism, and the “Technical” Barriers to Public Debate

For those of us interested in politics and rhetoric, the debate over net neutrality provides insight into the ways in which our political system processes “technical” issues and transforms them into partisan cleavages, identity politics, or economic wonkery.

One of the most frustrating aspects of the Net Neutrality debate is its “technicality;” politicians and citizens are hesitant to take a position on the issue because they find it too jargon-laden, complex, or plain boring. A Brietbart reporter reflects the majority view: “Unless you're a dork, you will have no idea what ‘net neutrality’ is.”

Many commentators have attempted to simplify the issue by explaining net neutrality in ordinary speech. Vox has a card stack on the issue. Jon Oliver devoted one of his long-form comedy segments to the issue. Many, many others use visuals, videos, and interactive graphics to educate the public on net neutrality.

Despite these attempts, some are speculating that President Obama’s involvement will reduce a “decade-long, wonkish policy debate” into a partisan battle between left and right. No one represents this shift better than Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas) who took to twitter to oppose the President’s statements, calling Net Neutrality the “Obamacare of the Internet.”

"Net Neutrality" is Obamacare for the Internet; the Internet should not operate at the speed of government.

— Senator Ted Cruz (@SenTedCruz) November 10, 2014

The comparison is revealing, not because it accurately reflects President Obama’s stance or the stakes of the issue, but for its insight into the nature of citizen preferences and partisan cleavages. That is, the extraordinary complexity of our healthcare system does not prevent ordinary citizens from taking a stance on the Affordable Care Act; likewise, net neutrality might be transformed into a partisan issue, whereby President Obama’s support could be used by political opponents to drive citizen opposition.

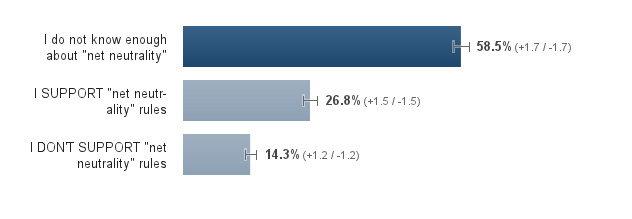

Both sides of the net neutrality debate are trying to argue that the American public is on their side. Who is correct is a matter of interpretation; because of the technical nuances, the wording becomes crucial. For instance, one survey suggests that the majority of the American public are opposed to fast lanes, but are simultaneously unsure about “net neutrality” as a political issue. Another survey argues that 61% of the American public oppose federal regulation and instead prefer that "the Internet should remain open without regulation and censorship." The fact that federal regulation is required to protect the Internet that Americans currently have—a status quo that is broadly supported across surveys—is obscured by the phrasing of the question.

In other words, surveys demonstrate that most people support the implications of net neutrality without explicitly supporting the policy of net neutrality. Now that the issue has taken a partisan flavor, the fate of the Internet might hinge less on citizen preferences than on a competition over whom the public hates more: President Obama or Comcast.

Free Speech, Free Markets, and Government Interference

Finally, questions over freedom, openness, and access are central to the debate over net neutrality. Scholars who care about freedom of speech and surveillance in the digital age need to pay special attention to the controversy.

There is also concern among conservatives that the President’s plan would open the way for more government censorship and surveillance because it explicitly allows for network manipulation in the case of “mission-critical services,” including local government emergencies. But most free-speech advocates, including the ACLU, fall squarely in support of Net Neutrality, with Sen. Al Franken (D-Minn) calling Net Neutrality the “First Amendment issue of our time.”

While some are concerned about what Net Neutrality means for Government surveillance, others direct their fear towards ISPs themselves. “The tools ISPs use to block and control our communications aren’t different from the ones the NSA uses to watch us,” argues FreePress. Kate Knibbs agrees, writing for Gizmodo that “ the government is not the only force that can constrict freedom. Corporations can be just as tyrannical as corrupt federal administrations, and we have been in danger of ISPs controlling and corroding the flow of information through the Internet in a way that would be detrimental to everybody.”

Thus net neutrality raises new, interesting questions over the changing dimensions of privatization and its relation to freedom, surveillance, and expression. Is government interference in content production inherently more dangerous than private interference? Can we really consider ISPs on the side of free market capitalism given the monopolization characteristic of the industry? And is the FCC the best agency to decide on this issue, given its own problems with democratic accountability?

Given how important the Internet has become to our culture, economy, and everyday communication, the next few months could have a profound impact on the trajectory of our digital lives. In addition to the debate over net neutrality, politicians and courts are currently negotiating other issues that have the potential to fundamentally alter the Internet. For instance, on Friday, a group of 77 prominent computer scientists filed a petition to the Supreme Court urging it to review a controversial decision in a case between Oracle and Google that would potentially allow APIs, an essential building block to software operations, to be subject to copyright.

Rochelle Terman is a web and communications consultant for the Townsend Center. She is a Ph.D. candidate in the Political Science Department at UC Berkeley, studying the consequences of global human rights shaming campaigns. Before joining the Center, she worked as a Drupal developer and communications consultant for the Social Science Data Lab, Social Science Matrix, and Information Services & Technology.