Stanley Fish's "Conceptual Triumph"

Jean Hyppolite, in Genesis and Structure of Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit, concisely ecapsulates the thrust of the master/slave dialectic by writing, " it consists essentially in showing that the truth of the master reveals that he is the slave, and that the slave is revealed to be the master of the master." One cannot help but recall Hippolyte's dictum when reading Stanley Fish's 13.June.2011 New York Times Opinionater entry entitled The Triumph of the Humanities.

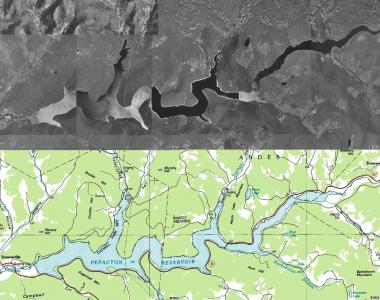

Fish opens his post with a description of the Catskill's Pepacton Reservoir, "a 20-mile ribbon of water between Margaretville and Downsville." Internet maps, Fish observes, will show where the reservoir is relative adjacent towns, "what they won’t show you, although every resident of the area knows about them, are the four towns — Arena, Shavertown, Union Grove and Pepacton — that were flooded in the middle ‘50s so that the reservoir could be constructed." This place with its mutliple realities--a visible surface and a submerged history--requires a different understanding of the relationships between culture, space, and time than that which a geographical map can provide.

Referencing the collection GeoHumanities: Art, History, Texts at the Edge of Place, Fish finds in GeoHumanities one (relatively) new discipline capable of fostering and elucidating this dialogic. This is highlighted in Edward L. Ayers's contribution to the collection. His "Mapping Time" shows changes that followed the emancipation of the slaves after the Civil War. Ayers and his colleagues, using digital imaging technology, began with a simple map of located population densities, and then they “put down one layer after another: of race, of wealth, of literacy, of water courses, of roads, of railways, of soil type, of voting patterns, of social structure.” This composite map with its clever use of layering can be "read" in multiple manners; it "can read events not merely historically, as the product of the events preceding them, but geologically, as the location of sedimented patterns of culture, economics, politics, agriculture."

Fish writes, "If interpretive methods and perpectives are necessary to the practice of geography, they are no less necessary to other projects supposedly separate from the project of the humanities." In fact, rather than rehash the so-called (and Sokal-fueled) 'theory wars', Fish observes how, in a Hegelian manner, "while we have been anguishing over the fate of the humanities, the humanities have been busily moving into, and even colonizing, the fields that were supposedly displacing them." Humanities, despite its lack of a "proportionate share of resources or intitutional support," has had, in Fish's interpretation, a "conceptual triumph" edging upon that of Hegel's slave. New disciplines such as GeoHumanities or BioHumanities use complex products produced within humanist fields to enhance their work. Oftentimes this commingling happens, as it did in Ayers's work, via the digital. Increasingly, it appears, the digital provides a catalyst through which disciplines can rearticulate themselves to answer prototypically humanist questions. In "Mapping Time," Ayers was able to use processing tools to layer items on maps, "converting time to motion...[and] reminding us of the structural depth of time and experience."

Though this fusion is cause for celebration, it is also a cause for concern. Many writers in the GeoHumanities anthology assert "that the division between empirical/descriptive disciplines and interpretive disciplines is itself a fiction and one that stands in the way of the production of knowledge." This may conceptually hold true, but, at the very concrete level of titling and departmental funding, these emergent disciplines tell a slightly different story. With names like GeoHumanities, BioHumanities, and Law and Literature, there is a distinct tendency to tag the word "humanities" onto another discipline, rendering the first word's discipline (Geography, Biology, or Law in these cases) as primary. One need look no further than the last presidential election to see the deep pessimism underlying such rhetorical constructions. As an "African American" candidate, Barack Obama's race as indice of any number of factors (citizenship, national allegiance, etc.) was [and remains] questioned; the underlying disconnect can, perhaps, be found in the sway of the initial "African" as somehow ontlogically primary over the word that follows.

Additionally, funding at most major institutions appears to follow this preferential logic. Given the already inequitable distribution of funding, this practice of creating hybrid disciplines only secondarily indebted to humanities while dismantling the traditional humanist departments will most likely continue. Though the humanities have had a "conceptual triumph" hastened by the digital, one cannot help but wonder if, following Hegel's allegory, one more step is necessary for a full triumph--a true emergence of something like Spirit. In Hegel's dialectic, once the slave realizes his hands created the world around him, he again struggles against the master. The inequitable relationship is resolved when both the master and the slave recognize they are different but equal.

The import of humanist concerns into other disciplines is promising, but true triumph, however that will look, is yet to come. Fish, perchance realizing this, concludes on a somewhat bittersweet note: "Perhaps administrators still think of the humanities as the province of precious insights that offer little to those who are charged with the task of making sense of the world. Volumes like 'GeoHumanities' tell a different story, and it is one that cannot be rehearsed too often."