What is left

“What’s Left? Personhood and Dementia” was sponsored by the Program for Medical Humanities and co-sponsored by the Townsend Center for the Humanities and the Center for Science, Technology, Medicine & Society. The conference was held in the Geballe Room of the Doreen B. Townsend Center for the Humanities, UC Berkeley, April 30-May 1, 2015.

During treatment, the philosopher’s father slipped a note under a barbed wire fence.

The fence served as an enclosure, of prisoners of war or of patients, and the year was 2005, or 1944, and the figures, speaking now gently, now firmly, were nurses, now prison guards.

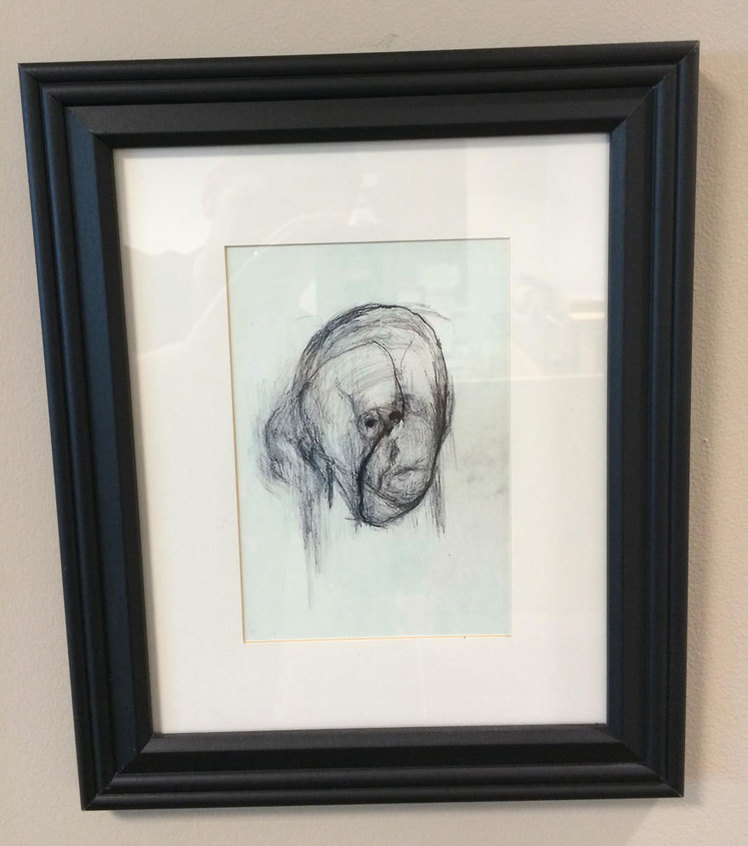

There are representations in literature and art of the driftwood state of those who claim to have no selves to speak of. As medical humanities scholar Marilyn McEntyre expressed during the panel on “Portraiture and Personhood,” the declarative is most often this: “I am not myself," the mark of a proximity to a void. Such statements are spoken silently in those moments when the physical environment, as a diabolical mirror, reveals a self that is an other—when reality bears the impression of a self that the one, perceiving, does not want to know.

We were told by the physician and neuroscientist, Andrew Kayser, that patients with dementia have three questions in the wake of their diagnosis: Why did this happen? How can you help me? What is going to happen to me? They seek to know the cause—what chain of events or chemical interactions delivered me here. They want succor, the form of deliverance that bio-medicine can offer. And finally, an oracle. They seek speech that will reveal what will take place and how what happens will affect the self who now inquires. These are questions about the relation of the self to her environment. These are questions, essentially about the world, as it is manipulated, as it will be made to speak—as it reveals to the one who asks, either a self or an other.

In the introductory remarks, the physician and professor Guy Micco, discussed dementia as a neuro-cognitive disorder, and offered the question: “what is it to have a self?” And seemingly, as addressed in so many of the talks by the presenters, to have a self involves some world, that makes us known to ourselves. Or else we search for some other cradle for being.

Kathleen Powers is a Ph.D. student in UC Berkeley's Department of Rhetoric and a Townsend Center Mellon Discovery Fellow.