Why is the Internet so Slow?

This past week, I was in Nairobi, Kenya attending a Technology and Human Rights Consultation hosted by Amnesty International. The consultation aimed to address the double-edged nature of the growth of digital tools in human rights activism. As our agenda put it, “there is a new human rights struggle emerging—one where human rights are both fought for, and violated, in the digital world.”

The Internet is slow for different reasons in different places. In the United States, the problem is usually “bandwidth hogs:” the five percent or so of users who are using about 50 percent of bandwidth, sharing movies and playing games online, rendering the connection slow for everyone else.

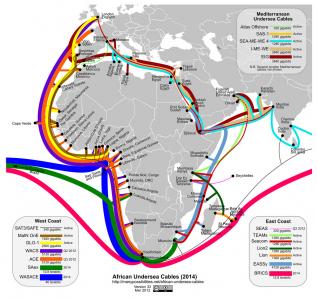

But in many other parts of the world, the problem is not with the users per se but with the infrastructure of the Internet itself. In South Africa, for instance, Internet speed is so bad that some companies have taken to pigeons rather than using email. (Seriously.)

The shortage of bandwidth in South Africa has to do with the dismal fiber optic cabling system. And the root of this problem, like most infrastructure problems, lies in political struggle. In this case it is the political struggle behind government-IST licensing agreements. According to Authur Goldstruck, who carried out a study on South Africa’s internet problem, governments’ attitudes towards the importance of Internet access plays a big role. “[I]t’s those vested interests, or policy interests, that tend to hold us back. It becomes a political process, instead of a technology and licensing process," says Goldstuck.

In 2006, the United Nations Secretary General convened the first Internet Governance Forum (IGF) as a multi-stakeholder policy dialogue to “foster the sustainability, robustness, security, stability and development of the internet.” This week, the Seventh Annual IGF Meeting will be held in Baki, Azerbaijan under the main theme “Internet Governance for Sustainable Human, Economic and Social Development.”

The irony that the IGF is being held in one of the most repressive countries for freedom of speech on the Internet is not lost on some human rights activists. “This is a country where the government intercepts individuals’ correspondence at a whim, imprisons bloggers, and portrays social-networkers as mentally ill,” says Amnesty International’s Max Tucker.

In addition to freedom of speech (which has been covered on this forum, both from a technological and human rights perspective) the IGF will have a major impact on the development of infrastructure and access. Indeed, there already appears to be a consensus among participants that IGF has a duty to further the development of and access to Internet infrastructure.

Rochelle Terman is a Graduate Student Researcher at the Townsend Center for the Humanities. She is pursuing a Ph.D. in Political Science.