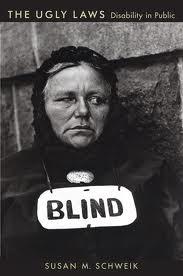

Berkeley Books: The Ugly Laws: Disability in Public by Susan Schweik

In 1881, the Chicago City Council ratified a law that aimed "to abolish all street obstructions" by prohibiting “Any person who is diseased, maimed, mutilated, or in any way deformed, so as to be an unsightly or disgusting object" from appearing in public. Known as the ugly laws, Chicago's ordinance and numerous others passed in cities across the nation, have understandably become a sort of shorthand for the oppression of disabled people and the criminalization of disability. But despite this prominence in the field of disability studies, the laws have been subject to little sustained study.

This month's Berkeley Books selection, The Ugly Laws: Disability in Public remedies this lacuna by telling the story of the “unsightly beggar” who emerged across multiple forms of discourse and knowledge in the late 1800s and early 1900s. In the Preface, Schweik, Professor of English, Associate Dean of the Arts and Humanities, Co-Director of the Disability Studies Program, and Co-Director of the recently-announced Disability Research Initiative, explains that book developed from an informal question posed to her by a colleague in disability studies and professor of city and regional planning, who asked: “Do you know, was that law ever actively enforced?” Schweik writes:

“I didn’t know, and it suddenly struck me as a problem that I didn’t. So I went to find out. This project emerged from the moment of that whispered question—an exchange between a city planner and a literary critic that in itself exemplifies some of the interdisciplinary range of disability studies.” (vii)

The book is divided into three parts, the first of which traces the emergence of the ugly laws, examining early examples and related municipal rulings. This first part moves from a discussion of the urban unease and class conflict surrounding conspicuous begging that gave rise to laws to an exploration of a wider range of factors that created a niche for them: the rise of eugenics and state institutions; the development of urban planning and an understanding of the urban public sphere as a pedagogical space; temperance and prohibition movements; and a rhetorics of disgust. The final chapter of the first part, “Dissimulations,” studies the figure of the faker, a constant preoccupation of ugly law advocates, who seemed to assume the majority of disabled beggars to be “sham cripples.” The second part, “At the Unsightly Intersection,” considers the other identity categories enmeshed with the “diseased, maimed, and deformed” to show how the ordinances have worked to reinforce unstable and evolving norms of nation, race, sex, and gender. The last part, “The End of the Ugly Laws,” traces resistance to the ordinances both at the moment they emerged and after.

In her review of The Ugly Laws in the American Historical Review, Barbara Young Welke writes: “This is a powerful book, essential reading for scholars of disability, race, gender, sexuality, immigration, urban, legal, social movement, and twentieth-century history more generally—indeed, for anyone concerned about law and its power and the limits of that power to define borders of belonging.”

In this week's Biblio-file Schweik recommends nine titles that influenced her thinking while working The Ugly Laws, and helped to shape the field of disability studies. Her selections include The Sunny Side of the Street, a memoir by a famous vaudeville performer often described as a ‘hunchback dwarf,’ Deborah Rhodes’ 2010 best-seller The Beauty Bias, and a collection of contemporary plays by disabled playwrights.