Big Data and Civil Rights

In a recent blog post on Solve for Interesting, writer Alistair makes a strong argument that "Big Data is our generation’s civil rights issue, and we don’t know it."

Big data, a topic we have blogged about before, "is a loosely-defined term. Generally, it is used to describe info sets so large and so complex that available database management tools cannot handle them. Difficulties 'big data' presents include hassles in the capturing, storing, and sharing of large information sets; additionally, even if securely stored, 'big data' presents further complications in searching, visualization, and analysis."

Alistair claims that big data requires "a reconsideration of the fundamental economics of analyzing data." This is because, "For decades, there’s been a fundamental tension between three attributes of databases. You can have the data fast; you can have it big; or you can have it varied. The catch is, you can’t have all three at once."

He terms these the three Vs: Volume, Variety, and Velocity. "Traditionally," he explains, "getting two was easy but getting three was very, very, very expensive."

Because of this, data was selectively collected. Companies, knowing they could not obtain all three Vs without accruing huge costs, would have to model what was important and how to collect it. Alistair writes, "This act of deciding what to store and how to store it is called designing the schema, and in many ways, it’s the moment where someone decides what the data is about. It’s the instant of context."

With big data, however, all three Vs are easily obtained at negligible cost. Alistair writes, "With the new, data-is-abundant model, we collect first and ask questions later. The schema comes after the collection. Indeed, Big Data success stories like Splunk, Palantir, and others are prized because of their ability to make sense of content well after it’s been collected—sometimes called a schema-less query. This means we collect information long before we decide what it’s for."

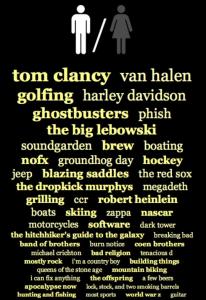

Alistair finds this new method--collecting first and schematizing later--highly problematic. The reason: companies can schematize large sets of data--songs we listen to, things we mention on Facebook and Twitter, purchases we make--in order to extract other, more personal information such as race, gender, age, etc. He writes, "If I collect information on the music you listen to, you might assume I will use that data in order to suggest new songs, or share it with your friends. But instead, I could use it to guess at your racial background. And then I could use that data to deny you a loan."

His solution: "link what the data is with how it can be used."

Given the massive amounts of data we proffer up to companies every day, the advent of big data and its uses does have the potential to become a major civil rights issue. And, given the pace of legislation--especially as pertains to information technology and restrictions--Alistair's warnings and concerns should not be taken lightly.