Digital Dark Age or TMI?

On October 1st, the Townsend Humanities Lab—our four-year exploration of digital tools for the humanities—will retire. Preparing to archive the site provides an occasion to reflect on digital archiving in general. What happens to all those unpublished website files saved on hard drives? Or how about the boxes of floppy disks out there? Do we even care? Some say that TMI (Too Much Information) is the Internet culture’s catchphrase, but others argue that it's worth preserving everything from dissident websites disabled by repressive governments to all the celebrity tweets about the name of the royal baby.

Organizations like the Internet Archive (hosts of the fascinating Wayback Machine, an archive of 240 billion web pages going back to 1996) and the California Digital Library argue that our digital culture is important, and they’re working to make sure it is available for generations to come. If we manage to successfully archive our current digital culture, researchers of the future could have intricately detailed snapshots of historical moments. Historians studying the revolution in Egypt, for instance, would have access not just to relevant documents and news reports, but a view of the whole world's reaction—moment by moment—on social media, blogs and web sites.

Yet, especially in places like the EU, some of this archiving runs counter to laws and ethics of privacy. In France, lawmakers are championing what they call “the right to be forgotten,” which would allow people to delete information about themselves (like drunken party photos) that they’d rather keep private. When they heard about this, French archivists took to the streets to try to preserve important historical information for the future. And they aren't alone. The NSA, other governmental bodies, and web companies like Google are also quite interested in preserving our ephemera. With such powerful interests in favor of information archiving, perhaps we’ll find the problem isn’t preserving our information after all, but gaining public access to it.

Despite all the corporate and state interest in collecting information, supercomputer designer Danny Hillis argues that we are nonetheless entering a “digital dark age” in which our archiving technologies won’t outlast us. How will future historians know anything about our society if we keep all of our information on media destined to become outdated and unusable? While we can keep transferring our data to more modern media as technology evolves (VHS—> DVD—> mp4—> ??), we won’t necessarily make the choice to preserve what future researchers will find useful. Scientists in the Netherlands, for instance, have used data from the CIA's recently declassified CORONA satellite spying program to track climate change. Yet according to the National Reconnaissance Office's Fact Sheet, this data is comprised of "2.1 million feet of film in 39,000 cans" that is subject to degradation and obsolescence over time.

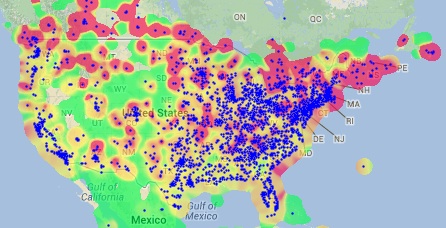

Today, we’re knee-deep in information about our digital culture. To see for yourself, visit Harvard’s Tweet Map; a recent comparison of “royal baby” and “economy” was depressing enlightening. Since we don't know what will be important to future researchers, it seems sensible to archive as much information as we can. Yet, given the amount of data we create, such a task might be too big and expensive a job.

For more on the topic of digital archiving, watch a video of Diana's Taylor's 2010 lecture, "SAVE AS... Memory and the Archive in the Age of Digital Technologies."