Labor of the Hands

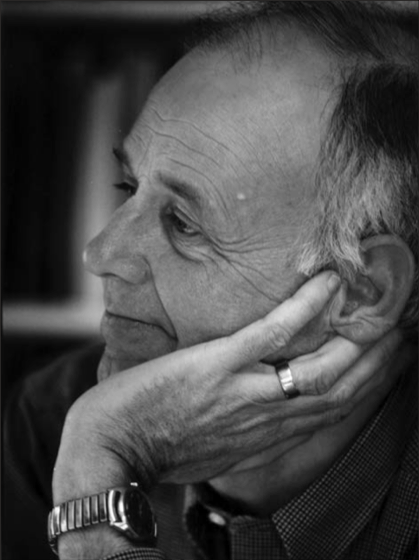

Celebrating 25 years of Avenali Lectures, the Townsend Center is pleased to present Wendell Berry as Avenali Chair in the Humanities, 2012-2013.

When I wrote the following pages, or rather the bulk of them, I lived alone, in the woods, a mile from any neighbor, in a house which I had built myself, on the shore of Walden Pond, in Concord, Massachusetts, and earned my living by the labor of my hands only. (Henry David Thoreau, Walden)

In Farming: A Handbook, Wendell Berry writes of “the man born to farming,” whose “thought passes along the row ends like a mole” and whose words flow out of his mouth “like water / descending in the dark.” Later, in The Unsettling of America: Culture & Agriculture, he summarizes what he sees as a series of commercial and agricultural exploitations: “This is not merely history. It is a parable.” Like Thoreau in his bean field, Berry works the field “if only for the sake of tropes and expression, to serve a parable-maker one day” (Walden). Yet unlike Thoreau, Berry assumes the role of the parable-maker whose morals and lessons are clearly instructed. His poetry has a straightforward message and a reverential simplicity in service to what he names variously as “home,” “earth,” “soil,” “darkness,” or “ground.” Whether writing poetry, fiction, or essay, a single and deep-running theme is his commitment to the local and to the small farmer’s agrarianism as the most healthy and economic lifestyle, consistent with Jeffersonian ideals of independent citizenry and democratic liberty.

Berry’s focus on farming and agricultural and ecological thinking is a lifetime dedication. He earned a B.A. and M.A. in English at the University of Kentucky, and in 1958 attended Stanford University’s creative writing program as a Wallace Stegner Fellow, studying under Stegner in a seminar that included Edward Abbey, Larry McMurtry, Robert Stone, Ernest Gaines, Tillie Olsen, and Ken Kesey. However, in 1965 he moved back to his native Henry County, Kentucky where he has lived and farmed ever since.

Though Berry’s farmer is one “whose hands reach into the ground and sprout, / to him the soil is a divine drug,” he interrogates our own knowledge and experience of such work. Of the modern eschewal of work and espousal of leisure and recreation, Berry writes:

Out of this contempt for work arose the idea of a nigger: at first some person, and later some thing, to be used to relieve us of the burden of work. If we began by making niggers of people, we have ended by making a nigger of the world. We have taken the irreplaceable energies and materials of the world and turned them into jimcrack 'labor-saving devices.' We have made of the rivers and oceans and winds niggers to carry away our refuse, which we think we are too good to dispose of decently ourselves. And in doing this to the world that is our common heritage and bond, we have returned to making niggers of people: we have become each other’s niggers. (Unsettling of America)

Using a term so heavily laden as it is, Berry’s comparison of work to the nigger cannot but be meant to shock and to remind us, as Lawrence Buell has written, of a dirty past—America’s slavery, its very own original and chronic sin. This is a formulation of labor as something we shun but must embrace, labor that we cannot make others do but must do ourselves. How circumscribed is labor of the hands? Besides farming, what other kinds of handiwork do we do? It is out of this circumscription that Berry would like to free labor, yet he does so by recalling a term that remains heavy and difficult to “handle.”

As difficult as it is to turn our old words and old forms into the new, to remake divisions and furrows, to restore and mend the ground, Berry takes up that work. His “labor of the hands” attends to the labors of tilling a field and writing a poem; it puts farming into a book and allows us to read poetry by hand. It shows that a small farmer today and a Negro farmer of the post-Reconstruction era have much in common; that to remake their farm-work is to also deal with and “manage” the sticky history of colonialism, slavery, and environmental degradation, as well as that of Jeffersonian pastoralism, piety, patriotism, and pure sweat and blood; that on the other side of revolutionary or emancipatory transformation is a people digging in and doing the work. It places things into hand, at hand, and even out of hand. It requires that we scale and measure ourselves in real physical relation to the vicissitudes of the world according to our own bodies and our own sense of space.

The grower of trees, the gardener, the man born to farming,

whose hands reach into the ground and sprout,

to him the soil is a divine drug. He enters into death

yearly, and comes back rejoicing. He has seen the light lie down

in the dung heap, and rise again in the corn.

His thought passes along the row ends like a mole.

What miraculous seed has he swallowed

that the unending sentence of his love flows out of his mouth

like a vine clinging in the sunlight, and like water

descending in the dark? (Wendell Berry, “The Man Born to Farming”)

Juliana Chow is a graduate student in the Department of English UC Berkeley. Her current research explores regionalism in late nineteenth-century American literature.

“An Agro-Ethical Aesthetic”

Wednesday, October 31, 2012

4:00 pm | Zellerbach Hall (*note venue change)

Wendell Berry in discussion with Miguel Altieri (Environmental Science, Policy, and Management), Anne-Lise François (English and Comparative Literature), Robert Hass (English), and Michael Pollan (Graduate School of Journalism).

Reading and Discussion

Thursday, November 1, 2012

6:00 pm | Berkeley Art Museum Theater, 2621 Durant Ave.

Both events are free and open to the public but tickets are required. Free tickets will be available at each venue one hour before the event.