The Land Remembers: Looping Violence in Madiano Marcheti’s Madalena

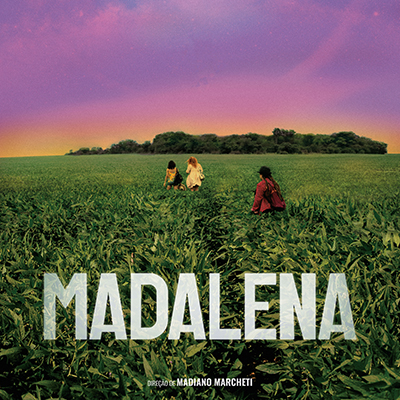

Madiano Marcheti’s film Madalena (2021) is a meditation on violence against trans people in rural Brazil, but it also explores the deep and lasting impacts of ecological violence. It tells of the death of a trans woman named Madalena as experienced by three people who knew her: Luziane, a club hostess whose mother sends her to pick up money from Madalena; Cristiano, the wealthy son of a soy plantation owner and a politician; and Bianca, a trans woman and close friend of Madalena’s. To a certain extent, Madalena might be categorized as a tragedy that captures an aspect of anti-trans violence in Brazil. But Marcheti didn’t start out with the express plan of making a movie about trans experience, even as he knew that he wanted to make a film about the LGBTQ+ community in his country. In a conversation put on by the UC Berkeley Social Science Matrix and the Department of Geography after a screening of the film, Marcheti explained, instead, that his aim in making the film was to capture a specific place at a specific time: a rarely filmed segment of rural Brazil, where violence done to the land mirrors itself in the lives of those who live upon it.

Again and again, Marcheti returned — through translator and event host Christopher Lesser — to the words “this place,” emphasizing the particularity of the rural location he represents in the film. Much like the place where Marcheti grew up in Mato Grosso, “this place” is all endless soy fields and near-identical housing developments, cut through only by the BR 163 highway. In their conversation, Marcheti and Lesser referred to the BR 163 variously as a “character in the film,” an “artery,” and a “scar” on the land.

This “scarring” of the land is integral to the story that Marcheti described wanting to tell. He began to write Madalena in 2014, which he called a political “boiling point” in Brazil, and continued writing through 2016, when a coup upended the government. In grappling with this moment of political and economic instability, Marcheti felt compelled to write about the violence that he said is “inscribed in the land.” This violence shows up in the way that the land has been homogenized, “made soulless” through its conversion to agriculture. In the film, the motif of monoculture is most visible in the soy fields, which flatten the landscape as the camera pans across it, or bisect it in the wide, shaky, unnerving shots that we get from the perspective of characters driving down the BR 163.

But this monoculture is also reproduced in the ways that the film’s characters live their lives, both in their homes and in their social structures. They are alienated from their land. For his UC Berkeley audience, Marcheti related some of his own childhood experiences of living in a recently formed, agriculturally focused city. All of the stories that he heard from the adults in his life were about other places, disconnected from the land where they were being told. This alienation, this sense of not being fundamentally “from” a place, Marcheti explained, allowed people — both in his own life and in his film — to excuse themselves from caring about the violence happening to the land.

This alienation is one example of what Marcheti is getting at in Madalena, of the way that violence done to the land mirrors itself in the lives of those who live upon it. There are hints of ecological violence from the very beginning of the film. There are the emus who wander among the soy fields and whose eggs are smashed by Cristiano as he discovers Madalena’s body. There are the massive combines that slouch across the land, consuming it. In one shot, a copse of trees in the distance serves as a relic of what the land must have looked like before most of the trees were razed to make way for agriculture. And there are the drones that hover over the workers in the soy fields, surveilling them. It is a choice that furthers what Marcheti called his attempt to “de-propagandize” soy, or to offer up a view of it that is not “aesthetically idealized.”

And this violence is replicated in the lives of the characters within the story. In his talk, Marcheti highlighted a scene in which Luziane and her mother speak about a group chat they are both in. One member of this chat has sent a picture of a dead man, sprawled half out of his car. It is an example, Marcheti said, of the banalization of violence in this place. And of course, there is Madalena, whose body we see only once. She stands out in relief, bruised purple against the soy. Her presence is essential to the point that the film is trying to make. Marcheti spoke about how, in his attempts to write about the land (and the harm done to it) he began to feel driven to write about trans people, who he felt were the most vulnerable to violence “in this place, at this time.” In order to understand the violence that is being done to the land, the film must deal with the violence enacted against trans people. These violences are linked intrinsically to one another, and to the wider political conditions in Brazil.

Marcheti talked about the BR 163 highway as a repetition of colonization and a demonstration of political and economic power. As his characters walk or drive along it, they retrace the cut that has been made across the land, and grapple with wounds of their own. Radios flicker on and off throughout the film, and mixed in with the music we get a political ad, repeated again and again. Cristiano’s mother is running for office, and her endorsement echoes through the background of the film. It is perhaps a nod to the political climate in Brazil both in 2016 and today.

The only respite from the claustrophobia and the violence comes in what Marcheti called an “ellipsis” at the end of the film. Madalena’s friends make their way off of the BR 163 highway and into a forest. In a little pond surrounded by bright green grass and twisting trees, they swim and remember their friend. It feels a bit like a healing.

Madalena does not seek to claim that ecological violence is the cause of transphobic violence, or vice versa. Instead, it emphasizes the feedback loop that connects the harm people do ecologically, personally, and politically. And it shows us the consequences that this feedback loop can have for the most vulnerable people. Most of all, it tells us that the earth remembers. What we pour into the land matters, Madalena suggests, because it will come back to us. It will filter back in through the very soles of our feet.