Love Deeper Than Logic: Sarah Ruhl’s "Eurydice"

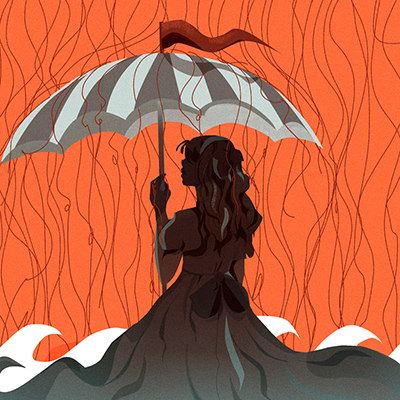

In March 2023, the Department of Theater, Dance & Performance Studies (TDPS) presented a production of Sarah Ruhl’s Eurydice. The play retells the classic myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, setting it in a world that feels distinctly, nostalgically, 20th century — far closer to us than the original classical context, but still somewhat removed in time. It is told from the perspective of Eurydice, and pays special attention to Eurydice’s relationship with her recently deceased father, a character that Ruhl created specifically for the play. Eurydice was written after Ruhl had lost her own father, and the play ultimately speaks to a seductive, destructive impulse that, perhaps, we all carry with us, an impulse that would have us follow the ones we love into the depths of oblivion.

Ruhl’s Orpheus and Eurydice are innocent and carefree: Orpheus (Tomás Francois), the best musician in the world, tells Eurydice (Daynna Rosales) that he wants to give her the sky, and then proposes by tying a bit of string around “a very particular finger.” Undercurrents of tragedy and danger come in the forms of Eurydice’s father (Nathanael Payne) — who has died recently and is attempting to send Eurydice letters from the Underworld — and a “Nasty Interesting Man” (Ryan Gottschalk), who uses one of these letters to lure Eurydice to her death. When Eurydice arrives in the Underworld, she is met by her father, whom she does not recognize. She has, in fact, forgotten most of her life, even down to how to read. From this point, the play alternates between scenes of Orpheus’s unsuccessful attempt to rescue Eurydice and scenes where Eurydice’s father helps her remember who she is. In death, the two ultimately build a kind of life together.

The TDPS production places its Overworld in a beachside, old-timey carnival setting, which serves to balance familiarity, nostalgia, and oddness. Its Underworld is surreal, reachable by a raining elevator, lorded over by a maniacal, tricycle riding Hades (Ryan Gottschalk), and narrated by a chorus of three Stones. Little Stone (Tay Kavieff), Big Stone (Bonnie Zhao), and Loud Stone (Leo Kearney) first appear as masked carnival workers in the upper world, and then in their true forms, as the long dead, in the Underworld. They are not minions of Hades, exactly, but they embody the imperative to forget, to submit to the anesthetic properties of the Underworld, that Eurydice and her father fight against for much of the play.

The play is daring in its use of novel theatrical devices to reveal the relationships between its characters. One of the most pivotal moments in the relationship between Eurydice and her father takes place when Eurydice, recently arrived to the Underworld, asks her father for a room. There are no rooms to be had in the Underworld, nor any building materials to speak of, so the Father builds her a room entirely out of string. The production trusts its actors (and its audience) enough to linger in the moment and allow the building of the string room to exist as the main action onstage for several minutes, with no dialogue, only music and a bit of peripheral clowning by the Stones. This scene is one of the most emotionally intense sequences of the entire play. We witness the full extent of the labor the Father undertakes to build something that, while physically insubstantial, soothes his daughter in her distress. It illustrates concisely one of the fundamental themes of both the original story, and Ruhl’s adaptation: that of a love that runs deeper than logic, that stretches past sense.

Moments like this one reveal how Ruhl has shifted the emotional core of the story in her adaptation. Eurydice centers more around the relationship between Eurydice and her father than it does around the relationship between Orpheus and Eurydice. In this version, it is not Orpheus who is at fault for the loss of his wife forever: it is Eurydice. She calls out to him as she follows him out of the Underworld and makes him turn around, in part, it is implied, because she cannot bear the prospect of being separated from her father again.

The play, which for so much of its run is focused upon the reacquisition of memory, ends in collective forgetting. First, Eurydice’s father, believing that his daughter has left for the overworld, bathes himself in the River, Eurydice’s version of the Lethe. His last soliloquy is poignant in its simplicity; he recites directions to what seems to be a place he visited when alive. He nears the River as he speaks of looking for Illinois license plates, seeing lights on the Mississippi River, passing a good climbing tree. As he forgets himself, we are left with the impression that we have been allowed to see some distilled, essential piece of him.

Eurydice follows her father into the River (in part to escape having to be married to Hades) and gives a similarly poetic soliloquy. Hers takes the form of a last letter to Orpheus in which she also gives a list of instructions for Orpheus’s next wife. Orpheus is the last to forget, arriving in the Underworld once again and having his memories washed away by the raining elevator before he can reach Eurydice. It is a tragic ending, full of near misses, but there is hope in it too. After Orpheus has lost his memories, he finds Eurydice’s letter. Upon finding that he cannot read it, he places it on the ground and stands on it in an attempt to absorb its contents. This is exactly how Eurydice tried to read upon first arriving in the Underworld. There is a connection being implied here, a drive to connect through language that can never be fully erased. It feels fitting, given Ruhl’s connection of the play to her own relationship with her father. Eurydice connects the playwright with a loved one who has passed, but it expands itself even further than that. It draws the audience, the actors, even the mythical Orpheus and Eurydice into this connection, creating an endless web of memory, love, and language.