Oral Cultures of the Digital Age

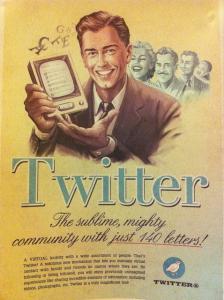

A pervasive assumption—one that I have voiced in this very space—holds that the inventions writing, the printing press, and the Internet represent watershed moments in a process of textual dematerialization, wherein meaning comes to inhere in the reproducible form of words, rather than gestures, orality, and the physical characteristics of writing. In a recent Sunday Magazine piece, “The Twitter Trap,” NY Times Executive Editor Bill Keller embraces this assumption, likening Johannes Gutenberg to Mark Zuckerberg and lamenting the loss of embodied thought and experience as we embrace digital technologies. He writes: "Sometimes I wonder if the price [of innovation] is a piece of ourselves."

Keller’s clear intent to provoke was signaled by a tweet that preceded the article: “#Twittermakesyoustupid. Discuss.” (In the last week, unsurprisingly, the contentious hashtag has reemerged triumphantly in a chorus of tweets like JustinNXT's: “Wow Weiner. Apparently @NYTKeller was right, #TwitterMakesYouStupid.”) Keller imagines his enraged readers as “passionate Tweeters,” “colleagues at The Times who are refining a social-media strategy to expand the reach of our journalism,” and “aging academics who stoke their charisma by overpraising every novelty.”

The tweeters, for the most part, responded in unwitting support of Keller's hashtag: "It produced a few flashes of wit ('Give a little credit to our public schools!'); a couple of earnestly obvious points ('Depends who you follow'); [...] and an awful lot of nyah-nyah-nyah ('Um, wrong.' 'Nuh-uh!!'). Almost everyone who had anything profound to say in response to my little provocation chose to say it outside Twitter."

As for Keller’s colleagues at The Times, Nick Bilton's letter reiterates the earnest obviousness of the tweeters while shifting the debate from medium to moderation and casting aspersion upon enduring Internet darlings—grammatically challenged cats: "Could Twitter make me stupid? Absolutely. If I only followed funny cats that speak with poor grammar, I’d be on my way to a vapid state of mind in no time."

Academics also responded, despite Keller’s rather malicious characterization of them. In a post entitled “It’s Not the Technology, Stupid!” Cathy Davidson, co-founder of HASTAC, makes a point that seems at once obvious and disingenuous when voiced by someone whose work grapples with the ways in which digital technologies are changing the humanities:

“But that's not about technology, it's about humanity. Between the human brain and the computer screen, comes us, our will, our desires, our habits, our training, our work, our incentives, our motivations, our culture, our society, our institutions, all of the things that make us human. It's NOT the Technology, Stupid! It is about what we—you and I—do with the technology. It always has been, it always will be.”

A more rigorous challenge to Keller's article is posed by Zeynep Tufekci, Assistant Professor of Sociology at the University of Maryland and author of the blog Technosociology. Her post, “Why Twitter’s Oral Culture Irritates Bill Keller” takes issue not only with Keller’s now infamous hashtag, but also the with overarching narrative that puts digital technologies on the same continuum as the inventions of writing and the printing press. She writes:

"[The] comparison between Gutenberg and Zuckerberg makes little sense unless you realize that Keller is actually trying to complain about the reemergence of oral psychodynamics in the public sphere rather than about memory falling out of favor. If the latter were the case, his ire would be more about Google; instead, most of his frustration is directed against social media, and mostly Twitter, the most conversational, and thus most oral of these mediums."

For Tufekci, then, the Internet is not the site of dematerialized text, but an assortment of platforms bearing diverse communicative implications.

Tufekci understands the specificities of sites as more significant than the fact of their being online, so that Google emerges as a print culture while Twitter and other micro-blogging and social networking platforms evoke oral traditions. Thomas Pettitt, Associate Professor of English at the University of Southern Denmark, on the other hand, considers digital culture itself to share more with oral than print traditions. Accordingly, he calls the age of print cultures the “Gutenberg Parenthesis," which, far from reaching its most advanced stage in a process of textual dematerialization, is now drawing to a close.