Sound Scholarship: Notes on the Field

This year, the Townsend Blog will feature a series of posts from members of its Working Groups. The Sound Studies Working Group addresses topics of cross-cultural work on speech and audition, technological advances in recording and composition, and contemporary and historical approaches to literature, music, and media. In this post, Serena Le, coordinator of the group, explores the idea of Sound Studies as a field for scholarly study.

“Sound studies” is a bit of an odd field. On the one hand, it is exactly what it claims to be—an umbrella field for the study of all things concerning sound—and there is something spectacularly exuberant about this. If we take “sound” as our guiding term and consider not only its heard properties but also its felt existence as vibration, our engagements can encompass anything from traditional categories for sound-based research (musicology in the Western classical tradition, phonology, architectural acoustics) to newer critical enterprises in performance studies and media theory, to contemporary noise art practice or gallery installations like MoMA’s recent Soundings. Ethnomusicological fieldwork, like Steven Feld’s study of expressive and environmental sound in Papua New Guinea, gives us insight into hearing as a cultural construct, while John Cage’s anechoic chamber experience and the work of performing artists like Evelyn Glennie and Christine Sun Kim challenge and help us revise popular discourses around silence and deafness. What isn’t, in some way, a matter of sound?

Hearing is embedded in our terms for understanding and evaluation (we “lend an ear,” and check for “resonance;” a plan “sounds good,” a statement “rings true”). As sound studies would have it, any branch of scholarship can stand to benefit from greater attention not only to what and how we hear but also to how we conceive of and communicate heard experience. For disciplines with established methods for describing and engaging with sound, sound studies functions as a bridge between specialized practice and broader interest or application. If we consider how the languages we speak or the physical environments we inhabit influence our perception of seemingly universal noises and rhythmic patterns, for instance, we can better understand the limitations inherent in systems for music notation. For disciplines with impoverished sound vocabularies (including my own discipline of English Literature), the field can introduce scholars to a wealth of new critical terms, technologies, and resources with which to shape discussion of previously latent or neglected phenomena. Sound studies also brings together those who work within the academy and those who come to sound through other professions: composers, engineers, and artists are just as likely to contribute to the field as institutionally affiliated researchers and pedagogues.

But what makes the field exuberant can also make it paralyzing. Over the past three decades, sound studies has acquired its own terms and movements, seminal works of scholarship, blogs, and, most recently, a few dedicated handbooks and readers. The staunch interdisciplinarity of this critical output can make individual contributions not only easy to take out of context but also overwhelming to consider collectively. In this sense, the field is still an experiment with uncertain results. Some of its greatest assets take the form of working groups, which can operate on multiple platforms to connect those interested in aspects of sound with the resources to develop such interests both richly and responsibly. This year, colloquia at Yale and Harvard join the University of Minnesota’s longer running effort to take better stock of the field’s potential. Our working group at Berkeley likewise hopes to serve as a hub for sound-related scholarship and activity. By publicizing everything from conference calls and campus lecture events to larger Bay Area performances and gallery programming, by building resource libraries that can be accessed both digitally and in person, and by keeping abreast of developments in sound research at large, our aim is less to define or crystallize a field of study than to promote interdisciplinary scholarship where sound is concerned.

If everything is a matter of sound, sound studies is as much about how we might identify, encourage, and disseminate complementary knowledges going forward as it is about specific projects, meticulously described.

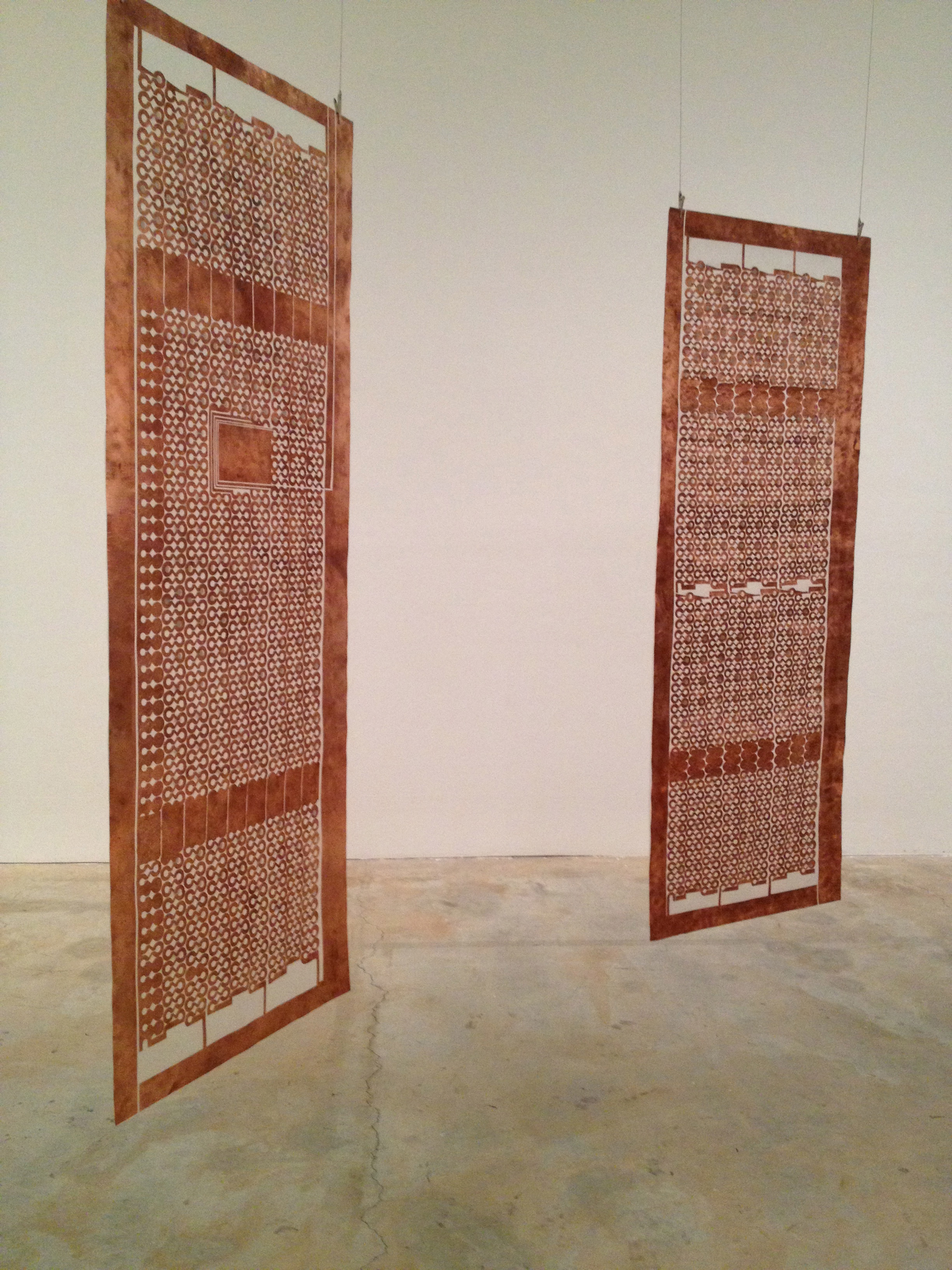

Image Credit:

Sound Tapestries by artist Jess Rowland. This sound installation, exhibited at UC Berkeley's Spring 2013 Art Practice MA Thesis Show, is part of Rowland's ongoing interest in building and composing for paper speakers. See more at www.jessrowland.com.