Spatial History: The New Look of the Old Days

Although it's too easy to proclaim that any new feature in a glossy, popular publication announces the true arrival of the digital humanities as a tangible force in the larger culture, the recent spot that Stanford's Spatial History Project landed in Fast Company--the progressive entrepreneurial tech mag--definitely warrants a little evangelism. And while the article may not represent a genuine watershed moment in the field itself (Stanford's Matthew Jocker, for instance, is even quoted as saying that his colleagues have "a long history of doing this work, but quietly, without the fanfare digital humanities is getting now."), a great deal of what is exciting about the digital humanities today comes through in the Spatial History Project profile.

A cardinal virtue of the write-up is that it is immediate and accessible, and Fast Company's David Zax has done a fine job of explicating the SHP's work and methodology in easily digestible terms. In his opening line, Zax cuts with commendable to clarity to the sine qua non of the new digital humanities: "[v]ast troves of data that are undeniably useful to history--but too complex to make narratively interesting." Here is a beautifully simple articulation of what the new school is all about. But credit doesn't lie exclusively with the author on this account. The Spatial History Project website is itself remarkable for its intelligibility and appeal to the non-specialist.

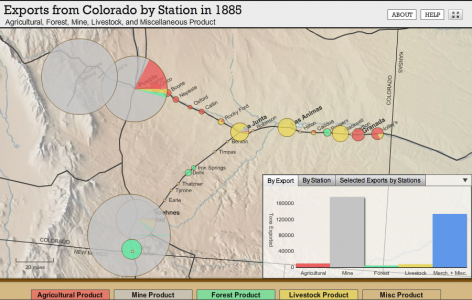

As Zax makes clear, Stanford historian Richard White and his colleagues are still telling stories in the best tradition of historical research, but the SHP team is using new methods to tell those stories--and to identify them in the first place. Part of the appeal for Zax (and for anyone wishing to use the scholarship coming out of the SHP as an exemplar of some of the new techniques) surely lies in the fact that White's subject--the development of the rail network in the American West--is fantastically well-suited to his chosen tools--digital mapping and GIS. Paired with a historical subject that we intuitively grasp as being spatially-oriented, White's methodology seems neither ostentatiously novel nor at all whimsical but entirely appropriate, even to the non-specialist. His attempt to "represent and analyze visually how and to what degree the railroads created new spatial patterns and experiences in the 19th-century American West" seems entirely like an enterprise whose time, technologically speaking, has come.

And this is important. White is not an upstart geek looking to storm the ivory tower and make a name for himself with faddish tools. Quite the contrary, Professor White is (and has long been) among the foremost historians of the American West, Native American history, and environmental history, and he has made ample contributions to those fields through decades of more traditional scholarship. What's particularly noteworthy about his "Shaping the West" spatial history project, then, is that in it, we see a long-established expert returning to one of the essential stories (the railroad) of his field and finding entirely new ways of understanding and relating the data in the sources.

Surely, this speaks volumes about the potential of digital techniques. And on that note, Berkeley scholars with an inclination toward the spatial-historical should not miss the opportunity to acquanit themselves with the Geospatial Innovation Facility here on campus.