Todd Gitlin's Revolts Against Revolts

In November of 2018, sociologist, author, and professor Todd Gitlin delivered the Doreen B. Townsend Center for the Humanities’ annual Avenali Lecture at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. The Avenali Chair in the Humanities is granted to distinguished figures in the humanities, and as this year’s Avenali Chair, Gitlin gave a lecture titled “The Other 1968s: Counterrevolution, Communism, and Desublimation.” In the talk, Gitlin discussed the relationships between counterculture, social conflicts, white supremacy, and the decay of communism (among other things), illustrating their connections to the current political moment in the United States.

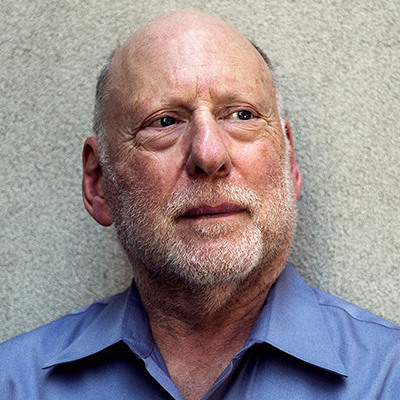

Throughout Gitlin’s life and work, it is clear that he is not just content with interpreting history; he also desires to shape it. He is currently a professor of sociology and journalism at Columbia University, but he has previously taught at UC Berkeley, New York University, Yale University, and elsewhere. He earned his PhD in sociology at Berkeley, has published in The New York Times and The Washington Post, and has written sixteen books, including one on the 1960s. His area of expertise is not just on the rage of the 1960s and its impacts, but on the indignation of this time period and the decade’s inherent hope for progress and moral action.

In “The Other 1968s: Counterrevolution, Communism, and Desublimation,” Gitlin argued that the revolts (and even the revolts against revolts) in 1968 created unintended consequences that would have lasting effects on American and international politics for years to come. To start, he described 1968 as having the texture of chaos. Protests occurred not just nationally, but globally: ranging from Memphis to Paris to Prague to Atlantic City and beyond. The growing prevalence of television allowed revolutionary ideas to be spread more quickly. Still, Gitlin claimed that these collisions between various political and social ideas didn’t register as strongly in America as we might assume. Changes did indeed occur, such as those pertaining to civil rights legislation, the growth of the Great Society, and the redesigning of environmental measures. However, Gitlin argued that changes were not indicative of a full scale revolution; rather, they indicated smaller cultural revolutions.

For some Americans, these small cultural changes were enough to spark a reactionary return to white supremacy and ideals of power through wealth. From Nixon’s “law and order” candidacy to Ronald Reagan’s claim that “Americans live in the future,” politicians channeled the sentiments of conservative Americans who were unhappy about the country’s shift toward increased voting rights, welfare programs, and environmental protection, among others. Politicians grabbed onto these ideas and used them to advocate for a nation of peace and prosperity, even well after 1968. This desire to quell progressive protests is evident in the nation’s politics, even today. Gitlin pointed to Donald Trump as a human reincarnation of smugness, performance, and consumption, all of which are remnants of the rich and happy lifestyles these Americans desired and for which they cast their votes.

While 1968 proved to be an unstable ledge for the United States between progressive revolt and plutocratic pushback, an international instability began for the communist movement. French communist revolutions were crushed, communist Cuba lost support from the Soviet Union, and Chinese leader Mao Zedong was exposed as murderous. Along with others, these events dimmed the glow of communism for many. Therefore, Gitlin argued that 1968 marked the beginning of the end for communism, adding to all his other reasons why the year was pivotal in shaping both the immediate history of the era and its continuing effects on politics and culture.

Given Gitlin’s arguments about the lasting impact of 1968, the question and answer portion of the lecture elicited some audience questions about the future of the United States. Gitlin noted that while the Trump administration casts a shadow over current progress, progress is still taking place with respect to how various groups understand electoral power, the supreme court, and other political institutions. He also compared the revolutionary mentality of the 1960s to that of today, saying that neither revolutionary group knew or knows what will happen in the future. Instead, all they can do is move toward their goals. Ultimately, current revolutionaries seem to mirror 1960s groups in the sense that a new age of organizing appears to be forming.