Traces of Authority

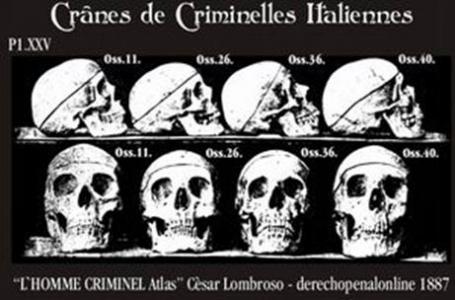

In a recent post in this space, I discuss the changing shape of the author as “distant reading”—and particularly Culturomics—concomitantly sever writer from text and enable new methods of authenticating their fusion. The aim of fusing writer with text has given rise to quantitative methodologies that resemble forensic science. Like the baroque phrenological catalogues of late 19th century positivist criminology, these new data mining techniques resolve to identify an individual, to discover "whodunit": in this case, who authored the text in question.

David L. Hoover's chapter, “Quantitative Analysis and Literary Studies” in A Companion to Digital Literary Studies, provides a useful introduction to author attribution methods that rely on digital technologies. For the most part, these methods involve counting the frequency of certain words and comparing words frequencies across a larger set of texts. As such, the focal point of a work, from the perspective of computational author attribution, is a smaller unit of text than that of more traditional literary criticism. Hoover writes:

“The frequencies of various letters of the alphabet and punctuation marks, though not of obvious literary interest, have been used successfully in authorship attribution, as have letter n-grams (short sequences of letters). Words themselves, as the smallest clearly meaningful units, are the most frequently counted items, and syntactic categories (noun, verb, infinitive, superlative) are also often of interest, as are word n-grams (sequences) and collocations (words that occur near each other).”

I conclude my last post by asking how our understanding of authorial authenticity will change as it is produced by data mining techniques rather than traditional philology, and what semiotic unconscious will be bared by so much data. More concretely, we might ask, will the reliance on smaller units of text in quantitative analysis of texts also influence the focus of more traditional interpretive work? Will narratology yield to phraseology? That is, will the frequency of various punctuation, letters, and words, deemed even by Hoover to hold "no obvious literary interest" seem more meaningful as they come to bear the most vivid traces of an artist's hand?

To answer this question we might consider its precursors in criminology, art history, and psychoanalysis—three fields linked by Carlo Ginzburg in "Clues: Roots of an Evidential Paradigm" because of a shared epistemological paradigm developed in the late 19th century: “a method of interpretation based on discarded information, on marginal data, considered in some way significant.”

Narratologists might take comfort in noting that a cigarette butt left at the scene of a crime—though it may help identify the killer—hardly changes the meaning of murder. Similarly, fingerprints and other forensic evidence may lead detectives to a subject, but are not necessarily essential to the experience or understanding of subjectivity.

Whether that is changing--in criminology or in the humanities--remains to be seen.