"The Two Cultures" Revisited

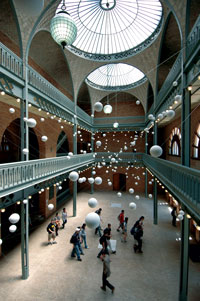

“Round Room” (mixed media, 2005)

by J. Ignacio Diaz de Rábago

It is now some fifty years since C.P. Snow delivered his famous Rede Lecture at Cambridge on the subject of the "two cultures”—those of the “literary intellectuals” and the “scientists.” Snow was exceptionally well positioned to speak to the issues involved. He had done high-level research at the boundary of physics and chemistry in the 1920s and ’30s and went on to a career as a successful novelist and critic. But the book that came out of his lecture captured the general attention of intellectuals because it spoke to much broader issues. It was at once historical and diagnostic. Among the issues it took in its sights were the absence of intellectual involvement in the shaping of the industrial revolution, the discrepancies among the major educational systems of the world, and the growing gaps between various specialized disciplines and the forms of understanding that are, or ought to be, more generally shaped.

It would be too easy to think about “The Two Cultures” today and to imagine that nothing has changed. Or to think that as some things have changed, others have remained just as they were. The notion that science and the humanities constitute “two cultures” may persist, but some of the differences between these intellectual worlds have been overshadowed by gaps of greater consequence. Specialization has certainly grown since the time Snow published his lecture. But in the end, humanists and scientists recognize themselves as part of the larger research university. The more worrisome gaps lie between the research university and its public.

Research universities have been agents for the advancement of expertise within various specialized fields of knowledge. They have nurtured the creation of new knowledge and the re-formation of outmoded frames of understanding. Much of the cross-disciplinary work that has taken root in the sciences and the humanities has brought about fundamental revisions in the ways we approach the world. These represent an important expansion of horizons. This new work also exerts a valuable counterforce against the ossification of disciplines that are not, in spite of their own hallowed traditions, anything more than intellectual “cuts” across the vast range of knowledge and research fields. Some of our institutional frameworks have adapted well to these challenges; others are still challenged by them. In the long term, it will be essential for all research universities, and for Berkeley in particular, to find ways to balance disciplinary structures and interdisciplinary efforts and to create the greatest possible degree of permeability across intellectual borders. This is particularly true where the disciplines in question span the “two cultures” that Snow had in mind.

But focusing on the intellectual shifts within the research university misses what we consider the most worrisome and challenging trend of our times: the ever widening gap between the research university and the public at large. This gap is spreading across the entire range of disciplines that the university encompasses. We realize that it is as difficult to speak to the general public about the specifics of particle physics as it is about negative dialectics. The reality is that most of the “general public” may not have studied math through calculus or have read Adorno to a degree that would allow them to grasp the frames for research, let alone the particulars. (Very few, if any, will have a sense of Adorno and calculus.) But the question here is not what the general public ought to know, but what it ought to know about what a research university does and how this benefits society. Closely related is the question of what a research university ought to bring to its public.

It would be all too easy to suggest that the relationship between the university and its public can be addressed through a relatively contained, instrumental notion of “education.” To be sure, a research university does provide instruction in basic subjects and cultivates a wide range of skills; it aims to enhance literacy, to ensure that students achieve a sufficient level of “numeracy,” and that they gain broad exposure to the cultures, concepts, and values of the world. But these things are taught in many other contexts, such as the liberal arts college, as well. They seem hardly enough to justify the mission of a great research university. By the same token, that mission seems to be offered for sale at far too low a price when its role is calculated strictly on the basis of “return on investment” to the economy of the state.

It should rather be through the spirit of questioning that drives new research, the reflection that refuses accepted ideas, and the critical practices that drive interpretation and creation in the arts, that a great research university understands the basis of its relationship to the public. An orientation towards research is more closely connected to the idea that knowledge changes over time than to the notion that there are final answers to be found. These qualities ought to be foremost in the minds of those who are entrusted with articulating the role of the university in public life. Students who are educated in these values—regardless of the particular mix of subjects they may study—will, in turn, become far better citizens for it. This is not only because they may become leaders upon graduation, but also because they will have been formed in the intellectual values that attach to research across the disciplines. If the research university is an economic engine, it can only be that because it is an intellectual engine that powers much more than the economy itself.

To imagine bridging the culture of the research university and the public culture at large is a daunting task, to say the least. But a research university must commit itself to the shaping of public values and not merely to reflecting the values already in place. It may serve us well to show that our biologists are at the cutting edge of advances in the field of stem cell research that will vastly help improve lives, that our economists advise presidents and policymakers on ways to alleviate poverty and improve health care, and that our cognitive scientists can pinpoint the location of certain memories in specific areas of the brain. “Innovation,” “discovery” and contributions to material progress are indispensable, but they are hardly the most important reasons to attach value to a great public research university. They are not the ultimate ones we would endorse when it comes to articulating the principles of our role in public life.

We may have allowed the sedimented ideas of C.P. Snow’s account, and others like it, to distract us from the larger ground of values shared by scientists and humanists in a research university. In the meantime, some very serious misunderstandings about the contributions of a research university seem to have been put in circulation. It is high time that we begin to address the gap between the university and its public by reclaiming the fundamental values we share, rather than devoting our energies to the differences in our internal cultures. Those “cultural” differences may well be real, but to worry over them now means diminishing the public force of the research university as a whole.

Anthony J. Cascardi is Professor of Comparative Literature, Spanish, and Rhetoric, and Director of the Townsend Center.

Fiona M. Doyle is Professor of Materials Science and Engineering, and Vice Chair of the Berkeley Division of the Academic Senate.

This article can be found in the February/March 2010 newsletter.